As winter fades into the green of spring with occasional final throes of cold weather, I’ve been reading Korean and Chinese poetry that focuses primarily on autumn and winter, which seems a fitting way to close the season.

If this is your first foray into Korean or Mandarin poetry, I suggest starting with more accessible books like the Ahn Do-Hyun collection I reviewed. For readers who want a challenge, read on to see if either of these fits the bill.

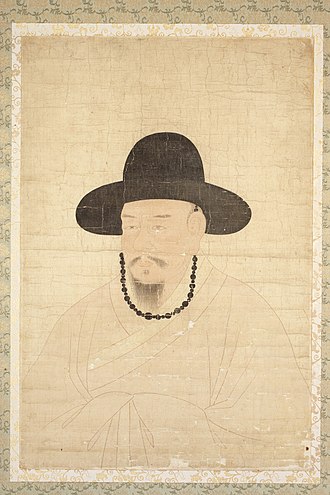

The Selected Poetry of Kim Si-seup: Classical Korean Poetry in Translation (translated by Richard Mayer)

While both of these books are a challenge, I found Kim Si-seup’s imagery more understandable than Mang Ke’s, which is surprising given that Kim wrote during the Joseon dynasty (1435-1493), while Mang Ke is a contemporary author (1950-present).

Kim Si-seup’s work featured in this collection is largely influenced by his worldview journey, which blends Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. I advise reading Richard Mayer’s notes before jumping into the poetry. I’m not quite sure why the notes are placed at the end because they are critical to understanding Kim Si-seup’s life and his poems’ subject matter. Mayer is a little confusing, but overall his explanations help clarify the more obscure poems and distinguish between the different “the Ways” of the three religions Kim writes about (note: Tao literally means “the way,” and both Confucianism and Buddhism have their own “ways,” all of which have distinct meanings).

You may not be all that interested in medieval Korean religious philosophy. Neither am I. I’m still glad I read the collection, though, because I like improving my understanding of other culture’s worldviews and thought systems, which can be drastically different from what we think of as “normal” in the West. I also like how Kim presents new perspectives on nature that are refreshingly different from anything I would normally read and help me picture the world in new ways. For instance, in the poem “One Day” Kim Si-seup uses a cartwheel metaphor that vividly conjured the image he describes: “The sky turns round like the wheel of a cart / And earth stands high like an anthill.” Having established the up and down motion of the cartwheel image, Kim closes the poem in a satisfying way that connects the wheel image with the poem’s theme about the repetitious nature of life: “So how many times in-between must the things / Of this world change? How many times rise and fall?” (19 Mayer).

Other imagery I liked includes “the mountain face gaunt” after the trees shed their leaves in “Idly Made” and another autumnal description in “Fallen Leaves” where Kim describes how “when rain inevitably falls / The empty mountain grows ten times thinner” (22, 35 Mayer). In a modern take on this fifteenth-century poem, my mind conjured up images of mountains on beauty queen diets, which made me smile.

One disconnect I could have easily resolved had I known to read the translator’s notes before jumping into the poetry is that, yes, the untranslated poems on each facing page are in Classical Chinese, not Korean like I would have expected. I had noticed the characters look more like Mandarin than Korean but assumed I was mistaken.

Kim Si-seup’s poems are short and fragmented, not always complete thoughts and rarely including punctuation other than periods at the very end or a question mark where needed (I imagine the punctuation is up to the discretion of the translator as there is no punctuation in the original Chinese). Rather than getting bogged down in the nuances of every line or where the thought breaks are (or aren’t, but might be?), I found it helpful to read lightly, keeping myself moving forward even when I was tempted to get caught up in each line. The result was impressions which were often interesting and in some ways freed me up to see the poem in broader strokes.

One instance of this happened with the poem “Untitled.” Kim describes the frozen water of a nearby spring, the latched bamboo gate, and how “my heart has much time to be free / And with each passing event freer” (25 Mayer). As the world becomes locked in winter, Kim discovers a new kind of freedom. He writes, “The eaves throw shadows through the window / When I first go outside and stand / Where at times I hear clearing snow / Fall down in-between the pines” (25 Mayer). Admittedly, this presents an obscure and fragmented image. However, the same day I read this poem, I had been reading about winter in Eleanor Parker’s Winters in the World about the Anglo-Saxon seasonal year. And as I finished Kim’s poem, I pictured the pines he describes shrugging the weight of snow off their shoulders and becoming freer—like the sense of freedom he is experiencing. Often, I picture winter as a gloomy, heavy season. Yet in this moment, Kim’s poem and Parker’s explanation about Anglo-Saxon views of winter, helped me see that winter can also be a time of rest (albeit forced rest) and letting go of weights like the pine trees shrugging the snow from their branches.

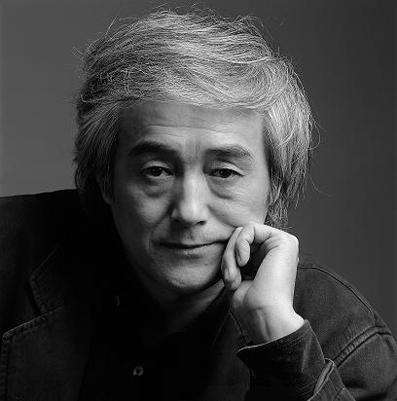

October Dedications: The Selected Poetry of Mang Ke (translated by Lucas Klein, Huang Yibing, and Jonathan Stalling)

Kim Si-seup’s poems are often obscure in their deeper meanings but accessible in terms of vivid imagery and descriptions of nature. Mang Ke’s poems, on the other hand, are obscure both in imagery and message. Throughout this collection of Mang Ke’s work, I felt like I was missing key pieces of information necessary to grasping the point of each poem—assuming there was a point and that the meaning is not left wholly to the reader’s interpretation.

What’s odd is that, based on the translator’s notes, I expected more expressions of political thought in Mang Ke’s writing. However, the poems seem more like the thoughts of someone suffering from depression than the rebel pen of a political zealot. Whatever political threads the poems contain are so obscure or lost in translation that I couldn’t find them, except when directly identified and explained by the translators. Perhaps this book would have merited footnotes for each poem or facing pages with explanations about any symbolism that might be obvious to Mang Ke’s original audience but overlooked by those unfamiliar with modern Chinese culture (for instance, the sunflower imagery which the translators helpfully explain is a twist on Mao’s use of sunflowers to depict his government).

In addition to the obscurity of the poems, several of them contain sensual moments where if you let your imagination follow the thread, you have a pretty good idea of what Mang Ke is referring to. All in all, Mang Ke’s poems are not my cup of tea. I really wanted to like them or gain insights from them, but felt I was fumbling in the dark instead.

Conclusion

As you’ve probably guessed by this point, I definitely preferred Kim Si-seup’s poems to Mang Ke’s. In fact, this post would have been much shorter (not 1,200 words), except that Kim’s poetry had some gems buried along the mountain paths and in the Buddhist monastery musings. While I disagreed with the predominant themes of both books, I got worthwhile philosophy and imagery insights from Kim Si-seup’s poems but little from Mang Ke, despite my best efforts.

Discover more from Worthwhile Words

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.