From the sword in the stone and the round table of Camelot to stories of knights on quests and courtly romance, Arthurian legend is filled with symbols and repeating themes of courage, honor, and growth in Christian virtue. The medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is no exception, containing many symbols and Arthurian motifs. Verifying that certain objects in literature are meant to have allegorical significance is often a challenge for researchers. However, literary expert Donald Howard views the presence of symbolism in Gawain as unquestionable. After all, he explains, “[T]he symbols are identified as such by the author” (425). Because of their layers of meaning, certain objects in the poem have drawn especial scrutiny. Author David Beauregard writes that the poem has “called forth a wealth of scholarly commentary, particularly in regard to the meaning of two of its allegorical symbols, the pentangle and the Green Knight” (146). Although the poem and most commentators focus largely on the symbols found in the pentangle, Gawain’s armor, and the Green Knight, Gawain’s green girdle is worth examining as well because it highlights several of the poem’s central themes. The girdle is a significant symbol in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight because of its color, connection to Christian imagery, and relation to Gawain’s journey of personal growth.

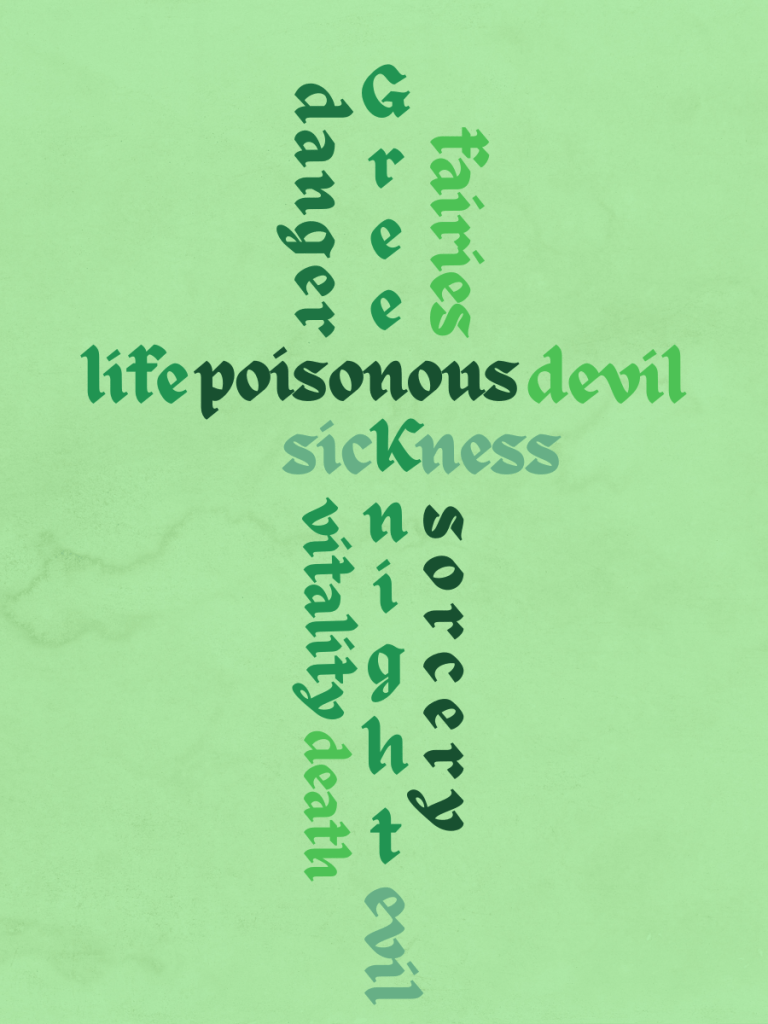

Color plays a noteworthy role in the symbolism of the green girdle, and many of the negative connotations of the color green add to the girdle’s meaning. Given the context of the poem, green represents the knight whom Gawain is seeking. This makes the belt a symbol of the Green Knight, as well as a sign of danger because Gawain associates the Green Knight with mystery and peril. In medieval times, green was also a color popularly associated with the devil and the fairy world, as Robertson mentions in his article “Why the Devil Wears Green” (471). To the poem’s medieval audience, this connection between the girdle and fairies would have represented an additional warning of danger. Green connects the girdle to the idea of illness as well. Robert Fleissner provides an example of this, writing that medieval humoral medicine associated sickness with being green (48). For example, Fleissner explains that “a ‘green lover’ could be either a bit off balance or severely ill” (48). Like the color green, the girdle embodies the idea of illness, for it weakens Gawain and reveals to Gawain “the frailty of his flesh” (Sir Gawain 2435). Another meaning green symbolizes is death, most likely because of the color’s connection to illness and the fact that plants popularly known for their evergreen nature are often toxic. As an example, medical doctors Evens and Stellpflug claim that mistletoe’s green leaves, in spite of medieval beliefs, are actually poisonous. Like its green color, the girdle represents death too, for Gawain is wounded because he takes it and experiences a metaphorical death when he meets the Green Knight at the end of the story. A final meaning of the color green that relates to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is fear. The Greek prefix chloro- means green, and author Helen King writes, “The ancient Greek adjective chloros was used for the colour appropriate to fear” (375). The girdle reflects this connotation and is a symbol of fear because Gawain agrees to take the belt out of fear for his life. Some might argue that Gawain accepts the belt out of caution, not because he is afraid, but Gawain himself admits at the end of the poem that he takes the girdle because of his cowardice (Sir Gawain 2374).

In addition to the negative meanings green represents, this color’s positive associations tie into the symbolism of the green girdle as well. The original audience would have seen the belt’s color as the sign of life because people relate green with vitality. For instance, in pagan and medieval times people viewed holly and mistletoe as symbols of life, and Lois Barber explains that the holly plant’s “green leaves and ability to produce fruit even in coldest winter evoked the promise of everlasting life.” Lisa Bonos adds to this idea, writing that the Druids believed mistletoe was “an antidote for all poisons.” The poem confirms that the girdle is meant to be a symbol of life, at least in Gawain’s eyes. When Bertilak’s wife presents the sash to Gawain, she claims it can protect its wearer from “anyone who seeks to strike him, / and all the slyness on earth wouldn’t see him slain” (Sir Gawain 1853-1854). Gawain demonstrates that he views the girdle as a symbol of life because he takes it, hoping that “it might just be the jewel for the jeopardy he faced / and save him” (Sir Gawain 1856-1857). As the belt’s color also demonstrates, the girdle is a sign of love. Writing about Malory’s poem The Tale of Sir Gareth, Sicile Herald, a French heraldry expert in the 1400s, states that green signifies love (Tiller 79). The context in which Gawain receives the belt further establishes this association with the girdle. After all, Bertilak’s wife gives Gawain the object at the end of her attempts to seduce Gawain, and Gawain agrees to hide the gift from Bertilak because he understands that it is an intimate object that would excite her husband’s suspicion.

Not only is the color green significant to the symbolism of Gawain’s girdle, but the girdle’s connection to Christian imagery is important as well. As Gawain prepares to embark on his quest, the poem emphasizes his armor. The mixture of Christian virtues with the physical components of Gawain’s armor, such as the five perfections that the pentangle on the shield represent, draws parallels between his armor and the armor of God in the Bible (Sir Gawain 632). This connection between Gawain’s apparel and the Christian’s spiritual armor is noteworthy because it explains another aspect of the green girdle’s symbolism. Describing the Christian’s armor, the apostle Paul tells his reader to fasten on “the belt of truth” (The Bible, English Standard Version, Eph. 6.14). Here in the poem, the girdle relates to truth because it is both a test and a sign of whether Gawain is truthful. Translator Simon Armitage writes that in medieval times, truth meant not just “a fact, belief or idea held to be ‘true’—but…faith pledged by one’s word” (136). Sir Bertilak uses the girdle to test Gawain’s truthfulness in both of these respects. By taking the belt and lying about it to Bertilak at their evening gift exchange, Gawain both lies and breaks his word. In this way, the green girdle becomes the belt of deceit, a foil to the belt the Christian is supposed to wear. The belt becomes a perversion of the metaphorical Christian armor in a second way as well. Donald Howard sees a parallel between Gawain’s arming himself before he sets out on his initial journey and his putting on the belt before he goes to meet the Green Knight. Because of the similarities in these two scenes, the girdle “becomes a substitute for the shield” (Howard 426). By wearing the girdle to protect himself, Gawain is replacing his physical shield with the belt. While this exchange makes sense from a practical standpoint because Gawain knows he will not be able to use his shield to protect himself, the replacement is extremely significant. Replacing the shield with the girdle reveals that Gawain is putting his trust in material items, not relying on what should be his true shield, the “shield of faith” (Eph. 6.16). If Gawain had relied on faith as his only defense, as a Christian should have, then he would have passed Sir Bertilak and Morgan le Faye’s test, symbolically using the Christian’s shield of faith to “extinguish all the flaming darts of the evil one” (Eph. 6.16).

Another connection between the green girdle and Christian imagery in addition to the armor metaphor is the way in which the belt parallels the temptation of mankind in Eden. Near the end of the poem, Gawain himself associates his situation with the Fall in Genesis, although he compares himself to Adam who “fell because of woman,” not to Eve who fell because of the serpent (Sir Gawain 2416). Bertilak’s wife plays the part of Satan, intentionally trying to seduce and deceive Gawain, and Bertilak himself confirms this fact, explaining to Gawain that the seduction was “all my work! / I sent her to test you” (Sir Gawain 2361-2362). Even the reasoning Gawain employs mirrors Eve’s logic, for Gawain justifies lying and breaking his word for the sake of a desirable end goal. Gawain falls for the same pragmatic reasoning that Satan employed when tempting Eve in the Garden of Eden, and the girdle becomes a sign of Gawain’s failure in the face of temptation, just as the fruit in Genesis is the symbol of Eve’s sin. A further connection to the Fall is that the fruit and the girdle are physical items that represent lack of faith in God’s perfect providence. Like the fruit, the green girdle is also associated with the breaking of an agreement, although in Gawain’s case, he breaks his agreement, not by taking the belt, but by lying and not giving Sir Bertilak all his gains on the third day. A final connection to the Fall is that the penalty for breaking the covenant in both Sir Gawain and in Genesis is death, and Mary Mumbach highlights this reality when she mentions that Gawain would have lost his head “if he had succumbed to temptation completely” (105). As the story plays out, though, taking the belt only leads to Gawain’s metaphorical death when he passes under the Green Knight’s ax three times, while Eve’s sin results in actual death.

In addition to color and Christian metaphors being crucial to the green girdle’s symbolism, the girdle’s role in Gawain’s spiritual journey is also significant. As with most quests, the goal of Gawain’s adventure is not the stated purpose of finding the Green Knight and keeping his promise. Instead, Gawain’s quest serves as a journey of self-discovery and spiritual growth. This is an idea Joseph Campbell articulates in his concept of the hero’s journey, commenting in an interview that the hero’s journey is the “quest to find the inward thing that you basically are” (Moyers). Because of the Arthurian context of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, though, Gawain’s quest involves spiritual growth, not merely self-discovery. The first role of the green girdle is to be the object of Gawain’s temptation. However, after Gawain fails to pass Bertilak’s test, the girdle becomes the catalyst for Gawain’s sanctification. In spite of his many virtues, Gawain still has areas of sin which he needs to overcome, and in the end, Gawain’s weakness in taking the green girdle shows him that he needs more faith and that man is weak because of his mortality (Sir Gawain 2435). Beyond being an object of temptation, the girdle also plays a part in Gawain’s growth by betraying him and by simultaneously representing Gawain’s betrayal of his promise to Sir Bertilak in the game of exchange. Because of the belt, Sir Bertilak has physical proof that Gawain has broken his word, and Gawain cannot deny his weakness. Confronted with the girdle as proof of his fall into sin, Gawain admits his guilt with a mixture of shame and anger and resolves to change (Sir Gawain 2370-2377).

The girdle’s relation to Gawain’s journey of personal growth does not end here, however, for the girdle transforms into a visual representation of Gawain’s changed character. Because of his close brush with death, Gawain has matured in his faith, and he makes the green girdle a symbol of his regenerate character. Gawain tells Bertilak that he will wear the girdle “as a sign of my sin” (Sir Gawain 2433). The belt also becomes a visual representation of Gawain’s new commitment to the truth. For example, when Gawain returns to Camelot, he does not attempt to hide his mistakes. Instead, he tells King Arthur and the other knights the entire story and maintains his resolution to wear the girdle for the rest of his life, which will constantly remind the people of Camelot of his sin, as well as of his honesty in admitting his guilt. The transformation of the girdle into a sign of Gawain’s truthfulness is important because the belt that has tested Gawain’s honesty and been the sign of his deceit has now become the “belt of truth” the Christian is supposed to wear (Eph. 6.14). This restoration of the belt to its proper meaning in the imagery of the Bible is another way in which the girdle demonstrates Gawain’s character changes and growth as a Christian.

True to its verdant nature, the green girdle grows in its meaning throughout Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and develops into an important symbol because of its color, parallels to Christian imagery, and connection to Gawain’s Arthurian journey of sanctification. Many of the historical meanings related to the color green highlight significant aspects of the green girdle. The parallels between the girdle, the armor of God, and the temptation in Eden add to the meaning of the belt by connecting Gawain’s journey to the life of a Christian and warning the audience to beware of hidden sin and temptation in their own lives. More importantly, however, the green girdle becomes a sign of Gawain’s new, changed life as it plays a role in and then becomes a representation of his Arthurian quest toward sanctification. By the end of the poem, the green girdle encompasses many meanings and affects not just Gawain but all of Camelot, for Arthur and his court adopt a green sash wore slantwise “as their sign, / and each knight who held it was honored ever after” (Sir Gawain 2519-2520). A controversial allusion to the Order of the Garter in the last line of the poem further reveals the girdle’s far-reaching effects as a symbol, for scholar Leo Carruthers argues that whether or not the line is original to the story, it demonstrates that readers have long seen a connection between Gawain’s girdle and the Order (66). The green girdle serves as a reminder of the frailty of man and is ultimately a symbol of the virtues of humility and truth which define every true Christian knight.

Note: This essay is one I wrote for a college literature class.

Works Cited

Armitage, Simon. Introduction to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2013, pp. 135-137.

Beauregard, David N. “Moral Theology in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: The Pentangle, the Green Knight, and the Perfection of Virtue.” Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature, no. 3, 2013, p. 146. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsglr&AN=edsgcl.329606342&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Barber, Lois. “Holly’s Symbolism at Christmas Goes Way Back.” Canadian Press, The. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://ezproxy.latech.edu:2080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=n5h&AN=MYO080531125608&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Bonos, Lisa. “How Did Mistletoe Become a Symbol of Love?” The Washington Post, 23 Dec. 2016, EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://ezproxy.latech.edu:2080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsgbc&AN=edsgcl.474823339&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Carruthers, Leo. “The Duke of Clarence and the Earls of March: Garter Knights and ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.’” Medium Ævum, vol. 70, no. 1, 2001, pp. 66–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43630340.

Evens, Zabrina N., and Samuel J. Stellpflug. “Holiday Plants with Toxic Misconceptions.” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 13, no. 6, 2008, pp. 538-42, doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.8.12572.

Fleissner, Robert F. “Falstaff’s Green Sickness unto Death.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, 1961, pp. 47–55. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2867270.

Howard, Donald R. “Structure and Symmetry in Sir Gawain.” Speculum, vol. 39, no. 3, 1964, pp. 425–433. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2852497.

King, Helen. “Green Sickness: Hippocrates, Galen and the Origins of the `Disease of the Virgins.’” International Journal of the Classical Tradition, vol. 2, no. 3, Winter 1996, pp. 372–387. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://ezproxy.latech.edu: 2080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=9610010586&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Moyers, Bill, producer. The Power of Myth. PBS, 1988.

Mumbach, Mary. “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” Invitation to the Classics, edited by Louise Cowan and Os Guinness, Baker Books, 1998, pp. 103-106.

Robertson, D. W., Jr. “Why the Devil Wears Green.” Modern Language Notes, vol. 69, no. 7, Nov. 1954, pp. 470–72. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://ezproxy.latech.edu:2080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=0000110615&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Translated by Simon Armitage. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2013, pp. 137-188.

The Bible. English Standard Version, Crossway Bibles, 2001.

Tiller, Kenneth J. “The Rise of Sir Gareth and the Hermeneutics of Heraldry.” Arthuriana, no. 3, 2007, p. 74. EBSCOhost, ezproxy.latech.edu:2048/login?url=https://ezproxy.latech.edu:2080/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.27870846&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Discover more from Worthwhile Words

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.